Notes and picture credits are presented in the final part of this series.

The South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club

The prospect of the South Fork Dam breaching had, by the late 1880s, almost become a running joke among those who along the Little Conemaugh River. Eyewitness Victor Heiser, then a teenager in Johnstown, would long afterwards summarize their cavalier sentiment: “Sometime, that dam will give way, but it won’t ever happen to us” (McCullough 1968, Unrau 1979).

Generally, though, people both at Lake Conemaugh and along the Little Conemaugh River spent the 1880s thinking about much more pleasant or routine things. At the lake, members and guests of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club began their summer weekends by boarding eastbound Pennsylvania Railroad trains in Pittsburgh. They disembarked in South Fork, a hamlet two miles downstream of the dam where the North and South Forks of the river converged. The members and guests then rode a carriage up along the South Fork to the northeast abutment of the South Fork Dam. There, they crossed the road along the crest of the dam and took in a fabulous view of the lake (McCullough 1968).

After crossing the dam, the Pittsburgh elites rode along the shoreline of Lake Conemaugh for another mile. Finally, they ended their journey at the Clubhouse, a large structure with bedrooms, a dining room, and a sizable lakefront porch. Initially, everyone stayed there during visits. Later, several Club members built ornate summer cottages overlooking the lake. By 1889, 16 cottages dotted the shoreline. They looked northeast across the lake, which was roughly 2.5 miles long and up to 1 mile wide, at a farmstead which could be reached by crossing the wooden bridge over the spillway (McCullough 1968).

Source: Hanna (2021)

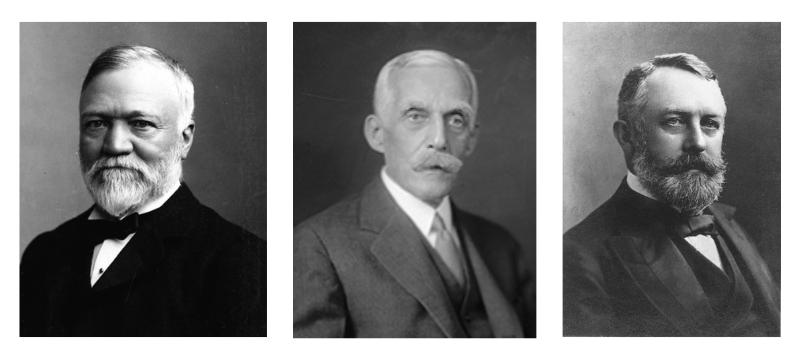

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was rustic by Gilded Age standards but remained high-class. Members included steel baron Andrew Carnegie, banking wizard Andrew Mellon, and coke fuel king Henry Clay Frick.

Sources (L to R): Biography (2021), Board (2023), NPS (2021 B).

They, their peers, and their families enjoyed fishing, hunting, sailing, rowing, shooting, and carriage and horseback riding. Many members enjoyed picnics beside the spillway. The men played cards and billiards in the evenings, and many probably smoked cigars. Everyone enjoyed relaxing on porches and taking in the lovely twilights and nights of the Pennsylvania mountains. They could see the crestline of the Alleghenies themselves from the Clubhouse porch. Benjamin Ruff’s death in 1887, while certainly sad, had scarcely disrupted the operations of the Club. Its biggest problems prior to 1889 were poachers and the lack of a sewer system, a need civil engineers worldwide were slowly addressing (Coleman 2018, Hanna 2021, McCullough 1968, Unrau 1979).

The 1880s in Johnstown

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was 8 miles east-northeast of and 450 feet in elevation above the borough of Johnstown. It must have seemed a world away, though, to many residents along the Little Conemaugh River. The constantly thrumming Cambria Iron plants filled Johnstown and nearby villages with clanking, smoke, and red glows from furnaces. Steel production was hazardous, and workers at Cambria Iron, who often toiled 60 hours or more each week, unfortunately were frequently injured or killed. Payday brought a lucky worker $10 per week, which equates in 2023 to about $16,600 annually. Yet the working-class people of Johnstown were decidedly optimistic. The valley and the US seemed to be making progress. By 1889, Johnstown had street cars, natural gas lighting and heat, and, in many parts of the borough, electricity. Johnstown’s citizens even owned 70 telephones. Daniel Morrell’s death in 1885 had been a sad and memorable event, but the business of Cambria Iron had continued apace. Meanwhile, the continued commerce in the valley fueled a regional population boom. By 1889, about 30,000 people resided along the 12-mile stretch of the Little Conemaugh between South Fork and Johnstown (McCullough 1968).

Lingering Problems

The future looked bright throughout the 1880s both at Lake Conemaugh and in Johnstown. Trouble, however, lurked at both places. At the lake, the South Fork Dam still had problems stemming from its poor reconstruction on Benjamin Ruff’s watch. The crew’s uncontrolled placement of fill in the 1862 breach had created a shear plane in the center of the dam, and ongoing consolidation of the fill caused an increasingly perceptible sag there. The sag eventually reached a depth of at least 1 foot, and possibly more. This further reduced both the capacity of the lake and the peak discharge of the spillway (Coleman 2018, McCullough 1968, Roker 2018).

Other factors also continued to weaken the South Fork Dam. Ruff’s crew did cover the downstream face of the filled 1862 breach with rip-rap during the rebuild, just as the original contractors had decades earlier. However, the rip-rap on the filled breach was smaller than that used on the original dam. The newer rip-rap thus exerted a lower normal force on the underlying fill than the original, heavier rip-rap surrounding it. The shear strength of the fill in the 1862 breach, already low due to the crew’s sloppy placement, was thus reduced even further. Moreover, new leaks kept appearing on the downstream face of the dam, indicating that potential slip surfaces were forming within the structure. These further compromised the already shaky integrity of the dam (Coleman 2018, McCullough 1968, Roker 2018).

Equally serious civil engineering problems existed in Johnstown. Floods on the Little Conemaugh and Stony Creek Rivers had occurred regularly since Joseph Schantz had founded his settlement a century earlier. By the 1880s, though, residents were felling forests throughout the valleys for lumber, and others were filling in the rivers to create prime real estate. Shrinking river channels thus had to handle growing volumes of runoff, and the floods in Johnstown had, predictably, become more frequent and severe.

Source: Strayer and London (1964).

The rivers swamped parts of the borough on seven separate occasions from 1880 to 1888. By 1889, the floods had become a frustrating, albeit not frightening, rite of spring. Later, the events of May of 1889 would become known as the Johnstown Flood, but the term would not reflect how often the town had been inundated before then (McCullough 1968, Shappee 1940).

May 30th, 1889: Eve of Disaster

Thursday, May 30th, 1889 marked the annual observance of the Decoration Day holiday, later to be known as Memorial Day. Most residents, and many visitors, in Johnstown spent the holiday enjoying a grand parade featuring many civic groups, most notably local US Civil War veterans. By contrast, just a few members and officers of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club were up at Lake Conemaugh, where the summer tourism season would soon begin. Several dozen laborers had been working at the Club since April to install a sanitary sewer line to serve the Clubhouse and cottages. The cost of the sewer system was around $387,000 (2023 USD), a cost nearly equivalent to that of the South Fork Dam reconstruction (McCullough 1968, Shappee 1940, Unrau 1979, Webster 2023).

The sewer installation project, unlike the dam rebuild, was being supervised by a trained civil engineer. John Parke was 22 years old and had three years of work experience. He was, in 1889, employed by the Pittsburgh engineering firm of Wilkins and Powell. Parke had no degree but had studied civil engineering for three years at the University of Pennsylvania, which qualified him to practice engineering per contemporary standards. The Club’s decision to hire an Johnstown Flood MDB 22 rebuild likely related to Ruff’s successor as President, Col. Elias Unger. Unger lived in the farmhouse on the northeast shore of the lake and had extensive experience a hotel manager for both the PRR and several successful private establishments in Pittsburgh. His decision to hire an engineer for the Club sewer project, and his large outlay for the project, suggest that Unger regarded the technical expertise of engineers more highly than Ruff had (Coleman 2018, McCullough 1968, JAHA 2013, NPS 2022 A).

Source: McCullough (1968)

The Decoration Day parade in Johnstown dispersed late that afternoon. A light rain had begun falling along the Little Conemaugh River from Johnstown to Lake Conemaugh by then. People all along the valley returned to their homes or lodgings, ate dinner, and retired for the night. John Parke went to bed at around 9:30 PM just as a stiff wind began blowing over Lake Conemaugh. He recognized that the wind likely preceded heavy rain. Yet Parke had become well-acquainted with the local weather during his two months on the sewer project at the lake. He knew by late May of 1889 that intense spring rainstorms in the region were fairly common (Francis et al. 1891, McCullough 1968).

The US Army Signal Corps, which monitored the country’s weather in 1889, knew, however, that something very uncommon was arriving over Cambria County at dusk on May 30th. Signal Corps officers in California had identified a major eastbound storm system on Sunday, May 26th. The system had dumped extreme rains along its path as it headed east. It had drenched Nebraska and launched lethal tornadoes across Kansas on Tuesday, May 28th. The next day, it had soaked the midwestern US east of the Mississippi River. By Thursday, May 30th, the Signal Corps knew that the California storm system would next strike Pennsylvania.

The weather situation over the southwestern part of the Keystone State then deteriorated further when the California system collided with two other storm systems advancing north from the southwestern and southeastern US, respectively. A mild system near the Eastern Seaboard compounded the situation by keeping the cluster of storm systems at a standstill. The cluster was stuck near the crest of the Allegheny Mountains, where orographic effects likely exacerbated the rains they brought. Lake Conemaugh was therefore in the worst possible location for the incoming storm (Roker 2018).

UPJ researchers would later describe the storm which was gathering as John Parke went to bed on May 30th as having an annual probability of below 1 percent (or, formerly, as being a 100-year event) but above 0.2 percent (or, formerly, as being a 500-year event). Johnstown did have a Signal Corps weather station in 1889 with which either Parke or Col. Unger could theoretically have checked that evening. However, weather checks were not part of the standard of care for operating dams in 1889, although they have since become part of the standard. Furthermore, Ruff’s decision to remove the discharge outlet meant that Parke and Unger would have had few options to keep the South Fork Dam safe from the incoming cluster of systems, even had they known of the storm (Coleman 2018, McCullough 1968, Roker 2018).

May 31st, 1889: The Storm Strikes

The storm cluster began dumping hard, heavy rain over southwestern Pennsylvania at around 11 PM on the 30th. The rain continued unabated overnight and, in Johnstown, it totaled about 3 to 4 inches. Residents in the borough knew that Friday, May 31st was off to a bad start nearly as soon as they awoke that morning. At least one landslide had caused property damage, and the Little Conemaugh and Stony Creek Rivers were audibly roaring before daybreak. At dawn, citizens noticed that both rivers were rising – an event never before noted in Johnstown – at over 1 foot per hour. Local schools and Cambria Iron, which were usually indifferent to foul weather, had sent their charges home by mid-morning. Downtown Johnstown was submerged in 2 to 10 feet of water by noon, making the day the worst flood in borough history. Hundreds of flustered, wet citizens made their way to taller buildings downtown or to the high, steep hillsides surrounding the rivers (Coleman 2018, McCullough 1968).

The storm had, however, been even worse near the South Fork Dam. Eyewitnesses living near Lake Conemaugh later reported an overnight rainfall of 6 to 7 inches, an amount supported by 21st-century analyses of the storm. Farmers in the surrounding countryside found as May 31st dawned that local streams, usually tranquil, were running well above their usual levels. One creek had swollen from 2 inches deep to 4 feet deep. Another creek 3 feet in depth was flowing through a field which had been dry on May 30th. Every stream in the 53-square mile drainage basin above the dam disgorged its overflowing waters into Lake Conemaugh. As the lake began rising, Col. Unger could use only the truncated, screened spillway to lower the water and protect the dam (Coleman 2018, Francis et al. 1891, McCullough 1968).

John Parke awoke at around 6:30 AM on May 31st. He noticed almost immediately that Lake Conemaugh had risen two feet overnight and that, from the Clubhouse porch, he could hear streams roaring miles away. Parke sensed danger and knew nearly instantly that the South Fork Dam might be in trouble, and he soon rode a horse to the dam. Parke found Col. Unger directing the sewer crew to do what little they could. Several laborers were driving a horse-drawn plow over the crest to supplement the dam’s dwindling freeboard. Others were using picks and shovels to deepen the swale where the auxiliary spillway had been. Everyone knew that the situation was dire. Unger nervously vowed that he would ensure that the dam received a thorough rehabilitation after the storm – assuming it did not breach (Francis et al. 1891, McCullough 1968).

Source: NPS (2022 A)

The rain was falling only intermittently by then, but the discharges from the local streams had not yet peaked. Lake Conemaugh thus continued rising, now at around 9 to 10 inches per hour. Unger, Parke, and the laborers toiled valiantly, but largely in vain. Years of carriage traffic over the crest of the South Fork Dam had tightly tamped down the surface, unlike the poorly-placed fill underlying it. The plow team could therefore pile just 1 foot of loose soil, if that, atop the dam, which would be of little use if the lake kept rising. Meanwhile, the laborers in the old auxiliary spillway had barely made their trench knee-deep when they hit bedrock. The trench was already overflowing. Even worse, the timber and debris carried by the water pouring into the lake soon overwhelmed the log boom and jammed the fish screens in the spillway, further lowering its discharge capacity. Some bystanders in the growing crowd at the dam begged Unger to remove both the screens and the bridge over the spillway. Unger refused to take such a seemingly drastic step, although he did reassign laborers to clear the screens (Francis et al. 1891, McCullough 1968).

May 31st, 1889: Growing Crisis at the South Fork Dam

The disastrous ramifications of Ruff’s cheap, sloppy approach to rebuilding the South Fork Dam and re-impounding Lake Conemaugh now became excruciatingly clear. New leaks began appearing near the dam base as the lake rose, which again matched Darcy’s Law. The peak discharge of the spillway, even with the emergency trench in the old auxiliary spillway, was proving pitifully inadequate to counter the rising lake level. The UPJ research team which quantified the capacities and peak discharges of the original and rebuilt dams and their respective bodies of water estimated that the volume of the lake was increasing by roughly 4,000 CFS by mid-morning on May 31st. At around 11:30 AM, the lake began overtopping the dam and the furrow of loose soil along its crest (Coleman 2018, McCullough 1968).

Col. Unger and John Parke had seen enough even before the lake had begun overtopping the dam. Unger asked Parke to ride to South Fork, home to the closest PRR telegraph office, and to have a warning message sent down the valley. Parke rode the two miles there in about 10 minutes. He told a small crowd in South Fork of the danger at the dam and asked two men to alert the local PRR telegraph operator. Parke then left, though, without making sure that the men were carrying out his request. The operator, Emma Ehrenfeld, did eventually receive word of the trouble. She admitted later to being exasperated that the old chestnut about the dam was coming up yet again, but she nonetheless sent a warning message to Johnstown, where the Pennsy station agent received it. Additional operators then relayed the message west to PRR executives in Pittsburgh (Francis et al. 1891, McCullough 1968).

Other concerned locals also sent telegrams warning about danger at the South Fork Dam down the valley of the Little Conemaugh late in the morning and early in the afternoon of May 31st. One was the local businessman who remembered the instructions he had received years earlier from Club member and PRR executive Robert Pitcairn.

Source: NPS (2021

For his part, Pitcairn likely recalled the June 1881 scare and certainly appreciated more keenly than almost anyone else what might happen if the dam failed. He received Ehrenfeld’s initial warning message and, within an hour, had hitched his private passenger car to the next Pennsy train headed east from Pittsburgh – well before his South Fork colleague contacted him. Yet Pitcairn, a notorious micromanager, never sent a warning message in his own name along the valley. A warning from Pitcairn would certainly have carried more weight among locals than the one from Parke, who was noble but little-known in the area, did, and would likely have prompted many citizens in the valley to take more seriously the threat posed by the dam (Coleman 2018, McCullough 1968).